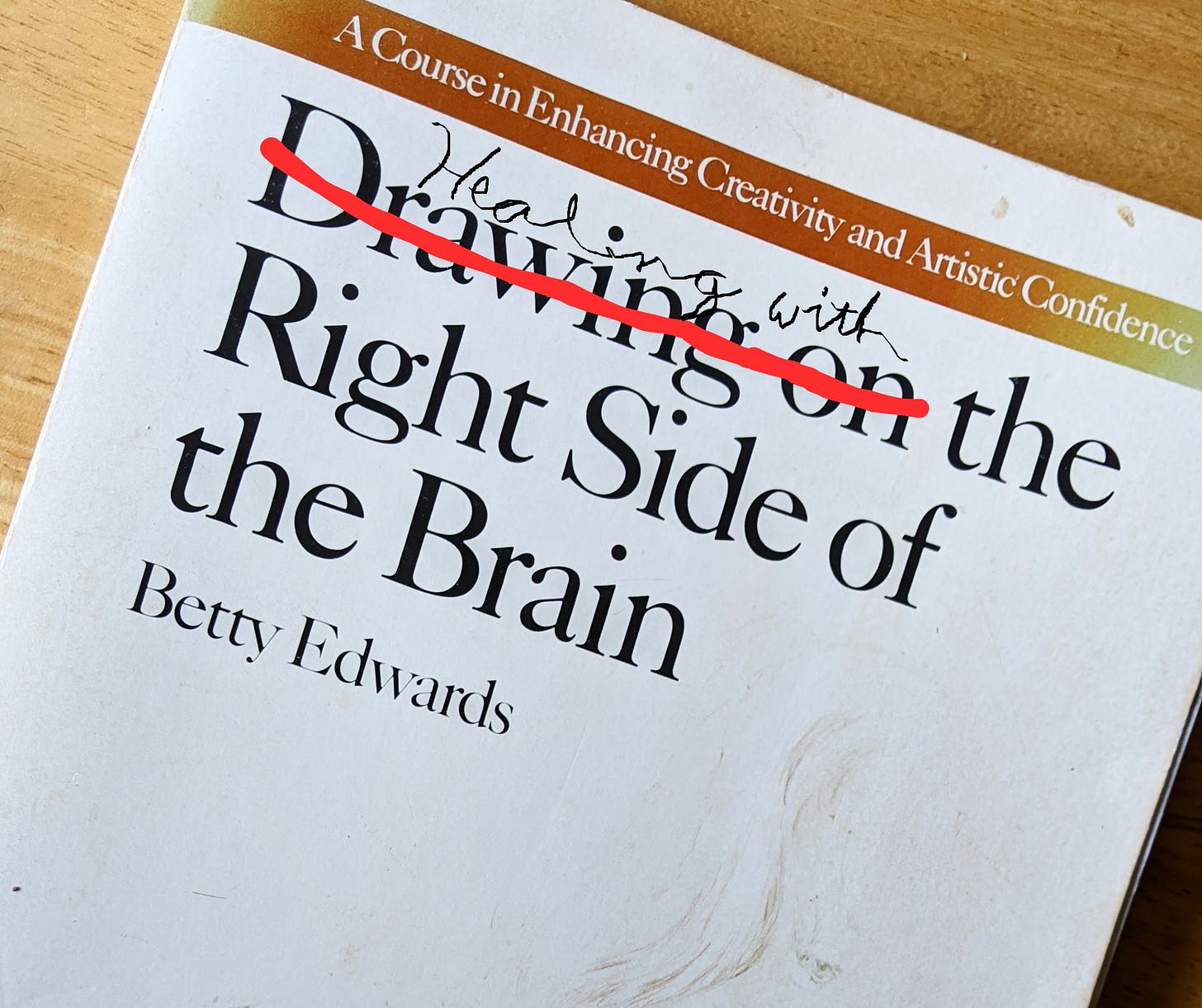

Over thirty years ago, I read Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain. My wife, Carol, had been given a used copy, and she found it helpful as did members of her weekly art group. I was not in any way a participant in this group for what I assumed were obvious reasons. I had given up on myself as a hopeless case when it came to drawing. Carol told me this book was meant for hopeless cases.

I picked it up and read a mixture of what I’d known (about left and right hemispheres of our brain) and much that I hadn’t. What hooked me in particular was reading that people like me (“hopeless cases”) couldn’t draw because the thinking dominated by our left hemispheres interfered with the process of drawing because of its unhelpful symbolisms and so-called knowledge about what we were trying to draw. The left hemisphere of my brain stopped me from “seeing” what I was trying to draw.

I was intrigued enough to try some exercises. I drew some pictures that were upside down, and I drew “negative space” – trying to outline what a thing “wasn’t” rather than what it was. These were tricks to confuse and shut down the left brain so the right brain, which actually saw what it was looking at, could take over. Lo and behold, just as the book promised, I made radical improvements within days and drew/painted some very mediocre pictures that I wasn’t embarrassed to share.

I was a newly minted psychotherapist at this time and, sadly, I made absolutely no connections (that I recall) to the process of therapy. Sigh.

On the other hand, for completely different reasons, I was getting intrigued with various therapeutic techniques that placed less emphasis on “talk” and cognitive understandings and more emphasis on imagination and metaphor. I was learning that potency to effect change and to get past places where people were stuck was greatly assisted by these approaches.

A decade or two went by, and by this time my favourite course to teach had become “Healing through Symbol and Story,” (part of this program) in which I taught the more experiential, “right-brained” (or “whole-brained”) approaches that I felt were crucial for healing when people were stuck. Then, I would come to read Iain McGilchrist’s The Master and His Emissary, and found the language and clarity to understand all that I’d been intuiting, teaching and seeing in my practice over the previous twenty years.

A couple of years ago, I added this section to the introduction of my course:

Words, ideas, and analysis are brilliant aspects of being human, but they are often a bottleneck to healing. There is far too much of our experience of being human that cannot be forced through this bottleneck. When we have become “stuck,” reason and language are more likely to be our jailers than our liberators.

Still, it took even longer before I would eventually wake up and realize that this was exactly what Betty Edwards was saying about drawing in her revolutionary book, Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain. It’s not just that the left brain doesn’t help; it actively gets in the way and interferes with clear insight and effective action.

When the connection between drawing and therapy finally1 dawned on me, I found our old copy and quickly re-read it.

Amazing! Every page felt like it was full of insights that applied as much to our journey through life (and therapy) as to drawing. We needed to stop our left hemispheres from using past understandings and over-simplifications to interfere - actively, arrogantly, and without concern for truth - with our right hemispheres. We’re missing out on what could get us unstuck.

Let me share just a few examples from Edwards’ book, with tweaks:

Drawing is not really very difficult. Seeing is the problem, or, to be more specific, shifting to a particular way of seeing. You may not believe me at this moment. You may feel that you are seeing things just fine and that it's the drawing that is hard. But the opposite is true, and the exercises in this book are designed to help you make the mental shift and gain a twofold advantage: first, to open access by conscious volition to the right side of your brain in order to experience a slightly altered mode of awareness; second, to see things in a different way.

That could easily be an introduction to therapy!

Or:

To put it another way, you already know how to draw (live/love/relate or heal/integrate), but old habits of seeing interfere with that ability and block it.

It’s that “interference” that therapists so often try to help get out of the way. They don’t (usually) need to provide the insights, just remove the obstacles that prevent them from being seen.

Trying to draw (gain a new insight about) a perceived form by using the verbal left mode is like trying to use a foot to thread a needle. It doesn't work. What is needed is for you to be able to "turn down" the left hemisphere and activate the right. This requires unblocking the right, or, as Aldous Huxley phrased it, "opening the Door in the Wall."

That Huxley quote mirrors a metaphor that was used of the early narrative therapists, often seen as miracle workers, who - Bugs Bunny-style - painted a door on a wall and opened it.

Here’s a line therapists would vouch for:

Your own unique set of symbols… was developed and memorized during childhood and is remarkably stable and resistant to change. These symbols actually seem to prevent seeing…

Finally, getting more specific:

Thus, the central problem of teaching realistic drawing to (counselling) individuals from age ten or so onward is that the left brain seems to insist on using its memorized, stored drawing symbols when they are no longer appropriate to the task. In a sense, the left brain unfortunately continues to "think" it can draw (make accurate sense) long after the ability to process spatial, relational information has been lateralized, or shifted, to the right brain. When confronted with a drawing (relational/emotional) task, the left hemisphere comes rushing in with its verbally linked symbols; afterward, ironically, the left brain is all too ready to supply derogatory words of judgment if the drawing looks childlike or naïve (one’s life remains stuck).

Do you feel the familiarity of that last phrase in bold? The left brain’s reliance on old, repetitive thinking and behaving keeps us stuck and then it judges us for being stuck! This is the essence of the addict’s dilemma – and also those who have been unable to escape unsatisfying relational patterns. Thanks for your help, left hemisphere! (not)

Please recall that my being a “hopeless case” at drawing is linked to the fact that I am very naturally inclined to a left-brained approach to the world. The safe, default world for me has always been logical, verbal and analytical. But I owe it no loyalty. When we’re stuck, we desperately need the ability to see the unique, present moment clearly and to respond to it in new and creative ways. This requires significant right-brained engagement (and that requires stopping our left brain from interfering). The eventual goal, once new insights and possibilities emerge, is to move toward integrative, “whole-brained” living – though soon our left brain may start whispering (and lying), “you know I knew that all along. Why don’t you let me steer again? I’m so much safer!”

Question to ponder: I wonder whether those who’ve used Betty Edwards’ exercised have spontaneously found themselves getting unstuck from some of their life problems? Also - you may want to read her book to find out you’re not a hopeless case at drawing!

(For left-brained sticklers: Yes, of course it’s true that the left hemisphere is not always our jailer. When something finally bumps our left-brained thinking out of its ruts, some good reasoning and planning can be very fruitful. And it can help save us from some very bad right-brained thinking that we’re also quite capable of. This is why McGilchrist keeps coming back to his central metaphor: the left hemisphere is a very important helper and support (the “emissary”) for the right as long as the right remains in charge of what matters most. And, by the way, it’s usually the right hemisphere that bumps the left out of its ruts.)

[This is part of a series of posts exploring a contemplative pathway to healing/maturing that I call “a compassionate consent to reality.” For an introduction to the project, you may want to see this post here, or perhaps better, a summary here. I’m so grateful for your interest and for any comments that you may have!]

I blame my left hemisphere for the slowness of this awareness because of how it rigidly compartmentalized therapy and drawing into different boxes despite all that I knew about “art therapy” – which was actually in another third box in my sadly compartmentalized brain. This third box was labelled “an approach that is not for you since you are a hopeless case at drawing.”

Intrigued, then hooked. Just ordered a copy of Drawing on the Right Side. I love your idea of wedding our creative and visual faculties with our quest for wholeness. I'm often stuck with my pencils and crayons, and even more often in life. Can't promise I'll contribute much in this space, but your integrated approach is exactly what's missing. Thanks Walter, and all the best for this project. You're on to something!

One of the most valuable books on our shelf, along side, The Matter with Things.

This revolution that’s going on might be just murmuring, but it’s what’s needed for our delight and healing.

Thank you Walter for your energy towards its blossoming.